Gender Identity

In 1777, long before the advent of sex change operations, Charles d’Eon de Beaumont abruptly changed his gender. Soldier, royal censor, diplomat, and spy, d’Eon was a famous figure in pre-revolutionary France. At a young age he became a member of the King’s Secret, a network of spies in the service of the French king. After fighting in the Seven Years War against the Prussians, he received the cross of Saint Louis, raising him to the rank of chevalier. Another stint as a spy, this time in London, kept the Chevalier fourteen years away from France.

In London, rumors began that the Chevalier was a woman, that “she” had become a “he” in order to join the ranks of spies and fight in the army. Londoners were eager to catch a glimpse of the Chevalier to confirm the gossip; bets were taken on the true gender of d’Eon.

At first denying these rumors, D’Eon later confessed all in a memoir: he had been born a girl but raised by parents who desperately wanted a boy. He had pretended to be male all along and was only now, as it were, coming out of the closet. In exchange for some secret papers of d’Eon’s that he desperately wanted, the French king issued a proclamation that the Chevalier was indeed a woman and authorized funds to be disbursed so that she could buy a full wardrobe of women’s clothes. Officially a woman, d’Eon returned to France. For the next thirty years, the Chevalier maintained a female identity, became obsessed with a form of feminist Christianity, and argued on behalf of women’s liberation. For d’Eon, this new identity was formed of equal parts personal desire (for instance, to dress as a woman) and general philosophy (a mixture of Christianity and early feminist thought). As scholar Gary Kates argues, “By becoming a Christian woman, and by repeatedly attempting to reenter the public sphere, d’Eon himself tried to live out his own imaginative ideas.” Only upon d’Eon’s death was it definitively proven that he had always been male, had fabricated his memoirs, and had misled everyone including his closest friends.

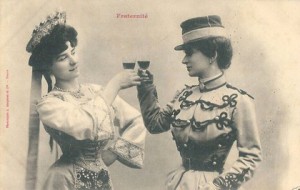

Our gender identity – that is, our notions of what is masculine and what is feminine – is handed down within families, inculcated in schools, and reinforced in myriad ways in our social interactions. Our very symbols for gender, the mirror of Venus and the arrow of Mars, suggest a socially constructed bias, with women linked to beauty and men to violence. In exceptional cases, such as Chevalier d’Eon, a person has thoroughly challenged the gender identity that society has molded for him or her. In some cases, social movements – for instance, the women’s suffrage movement – have challenged gender identity en masse: by arguing, in this case, for women to have the same voting rights as men. The Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender movement, in addition to challenging heterosexual assumptions about sexuality, has also made room for more expansive interpretations of gender, more diverse ways of being male and female.

Perhaps inspired by these movements, individuals question gender identities in many different ways. Men who cook, women who wrestle, girls who play with GI Joe and boys who prefer Barbie all challenge the gender roles that society attempts to enforce and suggest that gender is more a continuum than a binary opposition. There is also great differentiation in gender identity across cultures. There are no women in the parliaments of eleven countries in the world, yet in Norway more than 30 percent of parliamentarians are women. Female doctors and engineers are common in Russia but rare in Japan. Women have exercised considerable power as shamans in traditional Korean society; women are not represented at all in the ranks of power in the Catholic Church.

These differences extend even beyond the social sphere to the very biological determinants of gender. In Western culture, for instance, it was once very common for surgeons to surgically “correct” babies born with both male and female genitalia. Other cultures have taken a different approach. The Navajo, for instance, celebrate hermaphrodites as nadles who will bring luck to the tribe. Tahitians, the people of the Dominican Republic, and the Sambia tribe of New Guinea all recognize a third gender.

How much does biology influence gender? Is there a chromosomal continuum that mirrors the socially constructed continuum of gender? Do men and women have complementary strengths that are biologically and/or socially determined: can a man ever acquire a “woman’s intuition” or can the strongest woman ever bench press as much as the strongest man? Should we rejoice on behalf of gender equality when women can fight alongside men in the army or mourn this development as a loss for the peace movement? What would a gender-neutral school curriculum look like? What would a society look like that didn’t enforce separate and unequal treatment of gender?

On a trip to Provisions, you can explore the shaping of gender relations in Africa in Dorothy Hodgson and Sheryl McCurdy’s “Wicked” Women and the Reconfiguration of Gender in Africa, check out the resources in the magazine Transsexual Tapestry, participate in an on-line discussion of gender studies, chart the intersections of art and gender from the Axis foundation, listen to the Barbie Liberation Organization’s signature song, and see the gender-bending French film Ma Vie en Rose.